How Many Stomachs Do Cows Have

Ever wondered about the complexity of a cow's digestive system and how it influences their diet and life? This intriguing aspect of animal biology is both fascinating and relevant to our ecosystem. Cows, unlike humans, have a unique four-stomach digestive system. This extensive configuration supports a process called rumination, which is essentially a method of breaking down food using both mechanical and chemical digestion. This helps explain why their dietary habits and digestion significantly affect our environment. In this enlightening article, we delve into the 'Anatomy of a Bovine Digestive System,' breaking down its complexity and marvel. Then, we traverse through the intriguing process of 'Rumination and How Cows Digest Food.' Lastly, we connect the dots between a cow's digestive system, diet, and the wider environmental impact, providing a holistic view of the unique world of bovine digestion. So let's dive in and start by thoroughly understanding the structure and functionalities of their four-part stomach.

Ever wondered about the complexity of a cow's digestive system and how it influences their diet and life? This intriguing aspect of animal biology is both fascinating and relevant to our ecosystem. Cows, unlike humans, have a unique four-stomach digestive system. This extensive configuration supports a process called rumination, which is essentially a method of breaking down food using both mechanical and chemical digestion. This helps explain why their dietary habits and digestion significantly affect our environment. In this enlightening article, we delve into the 'Anatomy of a Bovine Digestive System,' breaking down its complexity and marvel. Then, we traverse through the intriguing process of 'Rumination and How Cows Digest Food.' Lastly, we connect the dots between a cow's digestive system, diet, and the wider environmental impact, providing a holistic view of the unique world of bovine digestion. So let's dive in and start by thoroughly understanding the structure and functionalities of their four-part stomach.The Anatomy of a Bovine Digestive System

In the expansive world of biology, there's a particularly intriguing aspect that singularly defines an important group of mammals: the Ruminants. Bovine creatures, a prominent member of this group, exhibit a remarkable digestive system whose sophisticated operation hinges on their distinctive anatomy. This article aims to dissect the complex structure of a bovine digestive system, titillating your scientific curiosity. It is manifested in three intriguing sections; "Understanding Ruminant's Unique Anatomy," which dives deep into its exceptional structure designed for extreme efficiency, "The Role of a Cow's Four Stomachs in Digestion," discussing the extraordinary working mechanism of these compartments, and lastly, "Key Differences Between Cattle and Non-ruminant Animal Digestive System," where we discern this distinctive system from non-ruminant counterparts, further emphasizing the uniqueness of the bovine digestive system. As we venture first into "Understanding Ruminant's Unique Anatomy," prepare for a journey that delves into the exquisite details and complexity of this remarkable biological feat.

Understanding Ruminant's Unique Anatomy

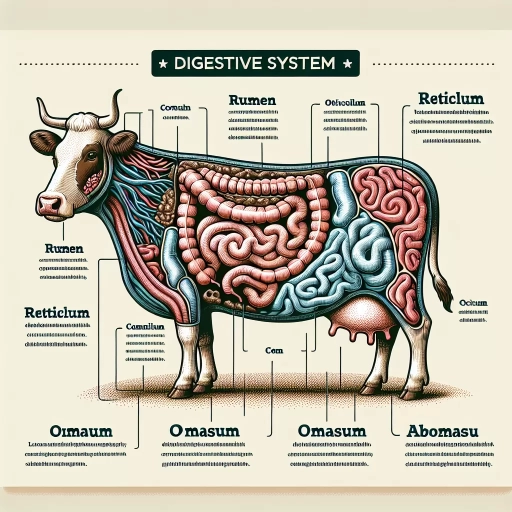

Ruminants, a unique group of mammals including cattle, are renowned for their distinctive digestive anatomy. At the heart of this uniqueness, and undeniably the centerpiece of the bovine digestive system, lies the complex, multi-chambered stomach. Structurally composed of four different sections - the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum - this intricate arrangement isn't just a random quirk of evolution. Instead, it is a sophisticated adaptation aimed at maximizing the extraction of nutrients from plant-based diets, traditionally difficult to digest. The rumen, the first and the largest compartment, serves as a fermentative vat populated by a diverse cocktail of microorganisms (bacteria, protozoa, and fungi). These microorganisms break down fibrous plant material through a fermentation process, transforming it into energy-rich volatile fatty acids and creates a stronghold of proteins through the synthesis of microbial protein. Directly adjacent to the rumen is the reticulum, a smaller compartment, but no less significant. Its honeycomb-like structure acts as a filter, trapping indigestible material and forming cud. This cud is periodically regurgitated, chewed, and swallowed once more – a process known as rumination - that significantly improves the surface area for microbial action and thus enhances digestion. The omasum, the third compartment, operates like a biological water extraction plant, removing water and electrolytes from the liquid passing through it. Its numerous folds play a key role in reducing the water content of the feed and in the absorption of fermentation products. Finally, the abomasum, often referred to as the 'true stomach', is most similar to human stomachs, secreting digestive enzymes and acids to further break down the nutrient particles. This enzymatic breakdown allows nutrients to be absorbed in the intestines thereafter. This magnificent quartet of compartments forms the basis of the bovine digestive system, giving these animals an unparalleled ability to extract nutrients from even the toughest of plants, unlocking energy sources that are inaccessible to many other mammals. Utilizing the fermentation power of the rumen, the filtering proficiency of the reticulum, the water extraction efficiency of the omasum, and the chemical digestion in the abomasum, the bovine digestive system manifests as an exemplar of evolutionary ingenuity. Understanding the dynamics of this unique anatomy holds the key to a range of aspects, including cattle health, environmental impacts, and productivity. More than just an anatomical curiosity, the four-stomached wonder is a marvel of natural design and a testament to the power of adaptation.

The Role of a Cow's Four Stomachs in Digestion

The Role of a Cow's Four Stomachs in Digestion is undeniably central to the unique biological makeup of these extraordinary creatures. Each cow's digestive system is incredibly intricate and specialized, and much of this specialization lies within their complex four-stomach system, consisting of the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. These four-legged ruminants are quite literally built to get the most nutritional value out of their diet of grass and plants, and understanding how each stomach plays a role in this process offers remarkable insight. The rumen, being the largest of the four stomachs, essentially serves as a fermentation vat where the ingested coarse plant matter is broken down by microbes into more readily absorbed nutrients. This fermentation process produces gases which the cow burps out. The cud, partly-digested food, is then regurgitated for further chewing thereby enhancing its breakdown. The cud next finds its way to the reticulum, known as the 'hardware stomach', where it undergoes further fermentation. Here, any foreign objects like stones or bits of metal that the cow might've accidentally swallowed get trapped, preventing them from entering other digestive organs. The third compartment is the omasum, a filtering powerhouse. It reduces particle size of the cud, extracting water and nutrients, allowing the cow to extract every possible ounce of value from its feed. Finally, the abomasum, commonly referred to as the 'true stomach' takes over. This stomach compartment functions similar to a human stomach, secreting enzymes and acids, which further digest the food, fully preparing it for nutrient absorption in the intestines. Clearly, the process that unfolds within a cow's four stomachs is multi-layered and highly specialized. This efficient system not only allows cows to derive nutrients from foods that other animals might find indigestible, but it also reinforces their special role in the ecosystem as converters of coarse plant matter into nutritious dairy products humans enjoy daily, underlining the crucial role each stomach plays in digestion within The Anatomy of a Bovine Digestive System.

Key Differences Between Cattle and Non-ruminant Animal Digestive System

Ruminant and non-ruminant animals exhibit significant differences in their digestive systems, all of which contribute to their unique dietary requirements and feeding habits. Understanding these differences can provide a more in-depth appreciation of how it influences the overall physiology and nutritional demands. Ruminants such as cattle have a complex digestive system that is particularly suited for the breakdown of cellulose and fibrous material commonly found in their diet primarily composed of grass and other plants. They possess a unique four-chambered stomach—comprising of the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum—that takes the lead role in the digestion process. Chewing the cud or 'ruminating' is a special process in cattle where food is regurgitated then re-chewed before sending it back into the stomach. This process ensures the maximum extraction of nutrients from their food. Moreover, the rumen serves as a fermentation vat where an enormous population of microbes synthesize vitamins and break down cellulose into volatile fatty acids which can be utilized as metabolic energy. On the other hand, non-ruminant animals like pigs and chickens have a simpler digestive process. These animals possess a typical monogastric (single-chambered) stomach that relies on enzymes to break down food. Unlike ruminants, non-ruminants cannot extract nutrients from high-fiber plants efficiently. Their enzymes are unable to break down cellulose, making a staple grass diet impossible. Instead, they rely on diets composed of grains, and in some cases, meat. Furthermore, non-ruminants do not chew the cud, hence their overall digestion and nutrient absorption are faster but less thorough. These key differences between cattle and non-ruminant animal digestive systems underscore the complex anatomy of a bovine digestive system. Having multiple compartments in the stomach, each with a specific function, allows cattle to effectively extract nutrients from a plant-based diet, making them the ideal animals for pasture-based farming. Conversely, the simpler system of non-ruminants supports quicker digestion, making them more suited for grain-based diet systems. Therefore, understanding these digestive systems can significantly contribute to better animal nutrition and management practices.

The Process of Rumination: How Cows Digest Food

Rumination, the remarkable gastronomical process that allows cows to successfully break down their food, is a fascinating blend of biology and nature's engineering. This article aims to take the reader on an intriguing journey inside the world of these gentle bovines, explaining how they process their food and deconstructing the complex process known as rumination. First, we'll present a detailed step-by-step analysis of the rumination process, seeing how nature has perfected this system over the centuries. Then, we will delve into the all-important role of regurgitation and re-chewing, discussing the intricate connections between this unusual behavior and the cow's digestive wellbeing. Finally, we'll take a sharp turn into the labyrinth of a cow's four-stomach configuration, which is a unique and essential component in the overall digestive process. After understanding these aspects, the complexity and efficiency of a cow's digestive system will no longer be merely a mystery but a fascinating fact of life. Now, we invite you to join us as we embark on this fascinating journey, starting with detailing the steps in the rumination process.

Detailing The Steps in the Rumination Process

Rumination, often referred to as "chewing the cud," is a unique and essential process in a cow's digestion system, which features a clustered four stomach compartments. It is a repetitive method that cow's employ, allowing them to break down complex plant fibers and extract the maximum amount of nutrients from their primary food source, grass. The first step in the rumination process occurs when the cow intakes food. Cows are polygastric animals which implies they chew quickly, swallow, and the food enters the first section of their stomach, the rumen. In this sizable compartment, packed with bacteria, protozoa, and fungi, the food is partially digested, through a process known as enzymatic fermentation. This partially digested mass, now referred to as cud, is regurgitated back to the mouth in sizeable boluses. Secondly, the cow re-chews the cud, a process that reduces the particle size and increases the surface area for the microbes in the rumen to act upon. This comprehensive chewing helps to mix the cud with saliva that neutralizes the acidity of the components and aids in enzyme breakdown. Following this, the cow swallows the cud again. This time, the semi-digested food bypasses the rumen and flows into the second stomach compartment, namely the reticulum. Bacteria in the reticulum further break down the cud and divide it into solid and liquid components which proceed into the subsequent chambers, the omasum, and abomasum, consecutively. The third step in the rumination process is more bacteria action in the omasum, where the water, minerals, and other residues from the cud are absorbed into the bloodstream. Finally, the last part of the rumination process takes place in the abomasum, how we might regard as the cow's 'true' stomach, similar to a human stomach. This compartment releases gastric juices, further breaking down the cud and absorbing the proteins and fats into the blood. The rumination process is a testament to the intricate evolutionary specialization within bovine. This detailed multi-stage digestion mechanism evolves to allow cows and other ruminants to convert tough, fibrous, and somewhat indigestible plant material into high-quality protein sources. So, the next time you witness a cow, seemingly in a state of leisurely contemplation, chewing away, remember, it is merely mastering the intricate art of digestion with its four unique stomachs.

The Significance of Regurgitation and Rechewing in Rumination

Rumination plays a central role in the digestion process of cows. One pivotal aspect of this is regurgitation and re-chewing. In rumination, the swallowed food is brought back from the rumen, one of the cow’s four stomach compartments, to their mouth to be chewed again, a process termed 'regurgitation'. This uncovering to additional salivation and chewing breaks down the food into finer particles. Herein lays the significance of regurgitation and re-chewing. Through this process, the surface area of the food particles increases significantly. This is a key factor to enable microbes present in the rumen to easily digest and extract nutrients from the food. The cow greatly benefits from the breaking down of cellulose-rich plant material by these rumen microbes, gaining vital energy that propels the animal's physiological and metabolic systems. Thus, rechewing during the process of rumination, fosters a cow's optimal extraction of nutritional gains from the plant material. Moreover, rechewing and salivation jointly aid in the neutralization of the acidity in the rumen, which can influence the overall health and productivity of the cow. Rechewing not only physically modifies the food particles but also introduces additional bicarbonate present in saliva to the rumen. This plays an important role in buffering rumen acidity. The beating heart of rumination, the regurgitation and rechewing, contributes to the establishment of an optimal environment in the stomachs of cows. It significantly influences the microbial fermentation process that occurs in the rumen, ultimately enhancing the digestive efficiency and productive performance of the cow. It's no wonder that any disruption to this precise and complex process can lead to an array of digestive problems. In conclusion, the significance of regurgitation and rechewing in rumination is demonstrated not only in its crucial role in the breakdown and digestion of food, but also in its contribution to the maintenance of balance in the rumen's environment. This may seem uninviting to the less bovine-savvy among us, but for our efficient, food-processing heroes - the cows - it's just another day job! Understanding the complexity of this process underlines the intricacies of the multi-stomach digestive system of cows and the pivotal role of rumination in ensuring cows are sustained healthily, efficiently, and productively.

Exploring The Twist: How Food Transitions Through the Four Stomachs

Exploring The Twist: How Food Transitions Through the Four Stomachs At the heart of the complex anatomy of a cow is a digestive system designed ingeniously for breaking down vast quantities of fibrous feed efficiently. This colossal task is accomplished by the cow's four individual stomach compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum, each playing a specific role in effectively harnessing energy from forage. The rumen is the largest of the four and acts as a fermentation vat. Here, bacteria break down the plant fibers, gently fermenting and brewing the i ngested forage. The intricate process begins when the cow wraps her rough tongue around the fodder, tearing it and gulping it down. This partially chewed feedstock is known as bolus and contains valuable nutrients captured inside plant cells. Next, the bolus moves to the reticulum, often referred to as the ‘hardware stomach’ due to its ability to trap foreign objects inadvertently consumed by the cow. This process prevents potential harm to the rest of the gastrointestinal tract. The reticulum and rumen work in unison, where the cud - regurgitated bolus – undergoes further robust rounds of chewing and salivation, breaking it down further. In the third compartment, the omasum, water and essential minerals from the now liquefied food are absorbed. The omasum acts as a sort of biological sieve, pressing out water and ensuring the gradual and controlled flow of semi-digested food to the next stomach. Lastly, the bolus arrives at the abomasum, usually regarded as the cow's "true" stomach since it's most like a human's in function. Here, acidic gastric juices break down the food even more, reducing proteins into amino acids and fatty acids from fats, preparing them for absorption in the small intestine. This remarkable food expedition through the cow’s four stomachs is a testament to the intricacy of nature's design, facilitating a digestive process which might otherwise be impossible, given the rather challenging fibrous diet of the cow. The stage-wise break-down and absorption of nutrients ensure that these ruminants maximize resource extraction from feed that would seem unviable to many other mammals, a fascinating twist of bovine biology.

The Impact of a Cow's Digestive System on Its Diet and Environment

When speaking about the impact of a cow's digestive system on its diet and the environment, one must delve deep into the intricate mechanics of bovine biology, environmental sustainability, and wise agricultural practices. This exploration is anchored on three vital topics: the intimate connection between a cow's digestive system and its preferred diet, the crucial environmental implications of cow digestion, and the compelling strategies employed by farmers and ranchers to manage and leverage bovine digestive processes. A cow's digestive system is an exquisite biological machine finely tuned by nature to extract precious nutrients from a diet largely composed of fibrous plants and grasses. This unique adaptation, which evolved to equip these heavy grazers with the ability to draw sustenance from an otherwise indigestible resource, serves as a biological marvel that illustrates the delicate balance between an organism and its diet. However, this fascinating digestive process doesn't exist in a vacuum—it significantly impacts the environment, with both potentially adverse and beneficial effects. The biological reactions inside a cow's stomach release considerable amounts of greenhouse gases—a factor that significantly contributes to climate change. At the same time, it creates nutrient-rich waste that can replenish soil fertility, presenting an interesting dichotomy that requires cautious management for sustainability. Finally, on the frontlines of this intriguing interplay between bovine digestion, diet, and the environment are farmers and ranchers. They utilize ingenious strategies not only to manage these processes but also to extract benefits from them, promoting the health of their livestock while minimizing environmental compromise. In this regard, we'll first delve into the fascinating connection between a cow's digestive system and its preferred diet—a cornerstone in understanding the deeper mechanisms at play.

Exploring the Connection Between a Cow's Digestive System and Its Preferred Diet

Exploring the connection between a cow's digestive system and its preferred diet reveals significant insights into the cow's impact on its diet and environment. Fundamentally, the structuring of the bovine digestive system, divided into four compartments, is intricately designed to process vegetation that many other animals cannot digest. This unique capability allows cows to thrive in diverse habitats, from lush meadows to sparse rangelands. Equipped with a complex digestive system, a cow primarily prefers a diet of grass and other plant materials. In the rumen and reticulum, the first two compartments of the cow's stomach, microbial enzymes work to break down these fibrous elements and converting them into nutrients. The magic does not stop here; when a cow grazes, it swallows the food without much chewing, and these first two compartments act like a fermentation vat, softening the food and making it easier to digest when re-chewed as cud. The third compartment, the omasum, has a key function in water and mineral absorption. The multi-layered structure enables it to extract necessary elements, thereby optimizing the cow's nutrient intake even from low-quality vegetation. Lastly, the abomasum works similarly to a human's stomach, utilizing stomach acids and enzymes to break down the cud into even more nutrients for the cow's body to absorb and use. By designing a diet that complements the cow's natural digestion process, we can enhance the cow's overall health and productivity. A diet rich in high-quality forage can promote healthy digestion and allow the cow to fully utilize its unique stomach compartments. Feed variety can also help the cow maintain a balanced microbial community, vital for optimal digestion and nutrient absorption. It is also important to note that a cow's diet directly impacts their environment. Consuming large quantities of grass and other plants, cows can help control plant overgrowth and maintain the natural balanced of varied ecosystems. However, improper management of cow grazing can also lead to overgrazing, causing soil erosion and degradation. With a concise understanding of how a cow's digestive system directly influences its dietary preferences, we can tailor a diet best suited to the cow's digestive mechanics, benefiting animal health, productivity, and environment preservation. Thus, digestive system is an important factor to consider in the wider view of sustainable livestock management.

The Environmental Impact of Cow Digestion

Research on cow digestion has unveiled significant information on its consequent environmental impacts. This fallout is predominantly due to a cow's unique digestive system which is characterized by a four-compartment stomach; the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum, each facilitating a different stage of digestion. Primarily, the rumen harbors microbes that aid in the breakdown of cellulose, the major component of a cow's high-fiber diet. This is where cow digestion contributes significantly to environmental changes. As the microbes break down the cellulose, they generate methane gas as a by-product, which cows then discharge into the environment mainly through belching and, on a smaller scale, through flatulence. Due to its high potency as a greenhouse gas (about 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period), methane is a critical focus in discussions concerning global warming. Livestock contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions surpasses that of the entire transportation sector, with cows being the primary culprits due to their unique digestive process. Further, the nitrogen in the cow manure also becomes a concern. When cattle discharge their waste, the nitrogen therein can convert to nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas almost 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. This issue escalates given the scale of modern livestock farming, where a large number of animals are kept in a confined space, leading to a concentration of manure that soil cannot absorb effectively. In addition, the process of growing feed for the cattle itself has environmental implications. It involves significant land use and deforestation, leading to habitat loss and biodiversity decline. Waterways near large scale farms can also become contaminated with run-off from manure, leading to algal blooms and aquatic dead zones where fish and other species cannot survive. However, it is imperative to acknowledge ongoing research and innovation aimed at mitigating the environmental impact of cow digestion. For example, some researchers are studying the potential for adjusting cow diets to decrease methane production. Others are developing ways to capture and use methane as a renewable energy source. These explorations highlight the intersection between animal science and environmental sustainability, driving us towards a more comprehensive understanding of cow digestion and its global impact. Therefore, while the cow's digestive system is a marvel in terms of its unique capacity to digest cellulose-rich diet, it's clear that this advantage also brings considerable environmental challenges. Future progress lies in our ability to leverage technological innovation and deeper understanding of this process to lessen the detrimental ecological impact.

How Farmers and Ranchers Manage and Benefit from Bovine Digestive Processes

Understanding how bovine digestive processes work is pivotal for farmers, ranchers, and those involved in animal rearing or agriculture. Notably, the cow's unique digestive system, featuring a four-compartment stomach, not only dictates its diet but also interacts substantially with the environment, providing both challenges and benefits for farmers and ranchers. Let's dive into the nutritious world of a cow's stomach. This multifaceted organ extends its significance beyond the animal's survival, marrying its metabolic needs with efficient waste management. First, the food consumed by cows, primarily composed of hay or grass, is initially broken down in the rumen. This large fermentation vat houses billions of bacteria and protozoa that convert cellulose, a substance indigestible to many animals, into nutrient-rich compounds. Farmers and ranchers can manipulate this process by controlling the diet and creating optimal conditions for these organisms to flourish, thereby enhancing the cow's nutrition. The secondary chambers, the reticulum and omasum, further refine these nutrient-rich compounds, allowing efficient absorption. The abomasum, or the 'true stomach,' then acts on these compounds with enzymes, similar to the human digestive process. This sequential and complex digestive process allows efficient food-to-energy conversion, limiting the waste generated and also enabling cows to subsist on a diet lesser quality compared to other animals. The cow's efficient digestive process also has significant environmental implications. Manure, a by-product of bovine digestion, is a rich source of organic matter and nutrients, making it an invaluable natural fertilizer. Consequently, farmers and ranchers can utilize this manure to improve soil health, reducing the reliance on synthetic fertilizers. Additionally, this process can be harnessed to produce biogas, a renewable energy source, through anaerobic digestion, presenting an excellent opportunity for sustainable farming. Finally, while cow's methane emissions, another by-product of digestion, are a recognized environmental problem, farmers and ranchers are now using innovative strategies to manage this. Through careful manipulation of diet and rumen microbiota, they can significantly reduce these emissions, turning a challenge into an environmental benefit. So, far from being a simple process, the bovine digestive process forms the foundation of many farming strategies, intertwining nutrition, waste management, and environmental stewardship. It provides a unique insight into how nature's processes, when understood and harnessed, can be used to our advantage in sustainable farming and effective resource management.