What Is An Moa

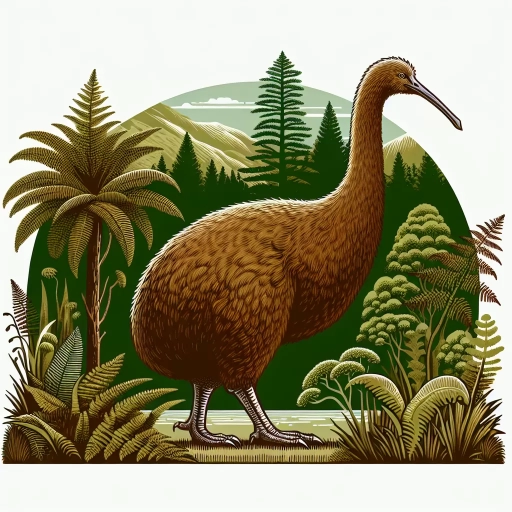

The moa, a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand, has captivated the imagination of scientists and the general public alike for centuries. These birds, which once roamed the islands in significant numbers, are now extinct, leaving behind a rich legacy of historical significance, fascinating physical characteristics, and a profound impact on their ecosystems. This article delves into the multifaceted story of the moa, beginning with an exploration of their historical context and discovery. We will examine how these birds were first encountered by early human settlers and how their remains have been a subject of scientific study. Next, we will delve into the physical characteristics and behavior of moa, highlighting their unique adaptations and social behaviors. Finally, we will discuss the extinction of moa, analyzing the causes and the subsequent impact on New Zealand's ecosystems. By understanding these aspects, we gain a comprehensive view of these remarkable creatures and their place in natural history. Let us start our journey into the world of moa by exploring their historical context and discovery.

Introduction to Moa: Historical Context and Discovery

The moa, a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand, holds a significant place in both the natural and cultural history of the region. This article delves into the historical context and discovery of these fascinating creatures, exploring their impact on various aspects of New Zealand's past. We begin by examining **Early Human Settlements in New Zealand**, where we uncover how the arrival of early Polynesian settlers influenced the moa population and the subsequent interactions between humans and these birds. Next, we discuss **First European Encounters with Moa Remains**, highlighting how European explorers and scientists first discovered evidence of the moa and how this discovery shaped our understanding of these birds. Additionally, we explore **Significance of Moa in Indigenous Maori Culture**, revealing the deep cultural and spiritual connections that the Maori people had with the moa. By understanding these different perspectives, we gain a comprehensive view of the moa's role in New Zealand's history. Let us start this journey by looking at **Early Human Settlements in New Zealand**, where the story of human-moa interaction first began.

Early Human Settlements in New Zealand

Early human settlements in New Zealand are a fascinating chapter in the country's rich and diverse history. The first Polynesian settlers, ancestors of the Māori people, arrived around the late 13th century. These intrepid explorers navigated the vast Pacific Ocean using sophisticated maritime skills and knowledge of celestial navigation. Upon arrival, they found a land teeming with unique flora and fauna, including the iconic moa, a large flightless bird that would become a cornerstone of their diet and culture. The initial settlements were primarily coastal, with communities establishing themselves in areas that offered abundant resources such as fish, shellfish, and other seafood. Over time, these early settlers expanded their reach inland, developing complex societies with their own distinct cultures, traditions, and technologies. The Māori people were skilled farmers, cultivating crops like kumara (sweet potato) and taro, which became staples of their diet. They also developed a robust system of governance, with iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes) forming the basis of their social structure. The arrival of Europeans in the early 19th century marked a significant turning point in New Zealand's history. This period saw the introduction of new technologies, diseases, and cultural practices that profoundly impacted the indigenous population. The moa, which had been a vital part of Māori life for centuries, began to decline rapidly due to overhunting by both Māori and European settlers. By the mid-19th century, the moa had become extinct, leaving behind only bones and feathers as remnants of a once-thriving species. Despite this tragic loss, the legacy of early human settlements in New Zealand continues to shape the country's identity. The Māori culture remains vibrant and influential, with many New Zealanders proudly claiming Māori heritage. The historical context of these early settlements provides a crucial backdrop for understanding the significance of the moa and its role in shaping both Māori society and the broader narrative of New Zealand's history. As we delve into the historical context and discovery of the moa, it is essential to appreciate the intricate web of human settlement, cultural development, and environmental interaction that defined this period in New Zealand's history. This understanding not only enriches our knowledge of the past but also informs our appreciation for the present and future of this unique and captivating land.

First European Encounters with Moa Remains

The first European encounters with moa remains marked a pivotal moment in the history of natural science and our understanding of New Zealand's prehistoric landscape. When European explorers and settlers arrived in New Zealand, they were met with tales from indigenous Māori people about giant birds that once roamed the land. These stories were initially met with skepticism, but the discovery of massive bones and eggshells soon validated the Māori narratives. One of the earliest recorded encounters was by the British navigator Captain James Cook, who heard accounts of these enormous birds during his voyages in the late 18th century. However, it was not until the early 19th century that tangible evidence emerged. In 1839, a British naturalist named John George Children received a large femur from a New Zealand missionary, which he recognized as belonging to a previously unknown species of bird. This initial discovery sparked a wave of interest among European scientists, leading to further expeditions and excavations. One of the most significant contributors to this field was Sir Richard Owen, an English biologist who, in 1839, formally described the moa and named it *Dinornis*. Owen's work not only confirmed the existence of these giant birds but also provided a scientific framework for understanding their place in evolutionary history. As more remains were uncovered, including skeletons, feathers, and even mummified remains, the scientific community began to piece together the life and times of these extraordinary creatures. The discovery of moa remains also had profound implications for our understanding of New Zealand's ecological and cultural past. The presence of these large herbivores suggested a complex ecosystem that had been significantly altered by human arrival. The Māori people had hunted moa extensively, leading to their extinction by the 15th century. This realization underscored the impact of human activity on native species and ecosystems, providing early insights into conservation biology. Moreover, the study of moa remains has continued to evolve with advances in technology and scientific methodologies. Modern techniques such as radiocarbon dating and genetic analysis have provided detailed timelines and insights into the evolutionary history of moa species. These studies have revealed that there were multiple species of moa, each with unique characteristics and adaptations to different environments within New Zealand. In conclusion, the first European encounters with moa remains opened a window into New Zealand's rich prehistoric past, highlighting both the scientific significance of these discoveries and their broader cultural implications. These early findings laid the groundwork for ongoing research into these fascinating birds, enriching our understanding of evolutionary biology, ecology, and human impact on the environment. As we continue to explore and learn more about these enigmatic creatures, we are reminded of the importance of preserving natural history for future generations.

Significance of Moa in Indigenous Maori Culture

In Indigenous Maori culture, the moa holds a profound significance that extends beyond its physical presence as a large, flightless bird. The moa, which became extinct around the 15th century due to overhunting and habitat destruction by early human settlers, is deeply intertwined with Maori history, mythology, and daily life. Historically, the moa was a vital source of food, clothing, and tools for the Maori people. Its meat was a staple in their diet, while its feathers and bones were used to create clothing, ornaments, and implements. The bird's large eggs were also a valuable resource, often used as containers or for ceremonial purposes. The cultural importance of the moa is further underscored by its presence in Maori mythology and storytelling. In traditional narratives, the moa is often depicted as a symbol of strength, resilience, and abundance. These stories not only reflect the practical significance of the bird but also its spiritual and symbolic importance. For instance, certain Maori tribes believed that the moa had spiritual connections, with some legends suggesting that it was a messenger between humans and the gods. Moreover, the moa plays a crucial role in Maori art and craftsmanship. Carvings and weavings often feature motifs inspired by the bird, reflecting its enduring influence on Maori aesthetics. These artistic expressions are not merely decorative; they carry deep cultural meanings and are integral to Maori identity. The loss of the moa had significant impacts on Maori society, leading to changes in their diet, lifestyle, and cultural practices. However, despite its extinction, the moa continues to be celebrated in contemporary Maori culture. Modern artists, writers, and performers draw inspiration from the bird's legacy, ensuring its memory remains vibrant and relevant. In addition to its cultural significance, the discovery of moa remains has contributed substantially to our understanding of New Zealand's natural history and the impact of human settlement on native ecosystems. Archaeological findings have provided valuable insights into the coexistence of humans and moa, highlighting the complex interplay between species and their environments. In summary, the moa is more than just an extinct species in Maori culture; it is a symbol of heritage, resilience, and the intricate relationship between humans and their environment. Its legacy continues to inspire and inform various aspects of Maori life, from art and storytelling to historical understanding and environmental awareness. As such, the moa remains an integral part of Indigenous Maori identity and a testament to the rich cultural tapestry of New Zealand.

Physical Characteristics and Behavior of Moa

The Moa, a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand, is a fascinating subject of study due to its unique physical characteristics and intriguing behavioral patterns. Understanding the Moa involves delving into several key aspects: its morphological features, dietary habits, and social structure. Morphologically, the Moa's size, feathers, and skeletal structure set it apart from other avian species. These physical traits not only influenced its daily activities but also played a crucial role in its survival and adaptation to the environment. Additionally, examining the Moa's dietary habits and foraging behavior provides insights into how these birds interacted with their ecosystem, highlighting their role as herbivores and their impact on the vegetation of their habitats. Furthermore, exploring the Moa's social structure and mating habits reveals complex interactions within their populations, shedding light on their social behaviors and reproductive strategies. By focusing on these three areas, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of the Moa's biology and behavior. Let us begin by examining the morphological features of the Moa, specifically its size, feathers, and skeletal structure, which form the foundation of its remarkable physical presence.

Morphological Features: Size, Feathers, and Skeletal Structure

Morphological features of the moa, a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand, are pivotal in understanding their physical characteristics and behavior. One of the most striking aspects is their **size**. Moa species varied significantly in height and weight, with the smallest species, the little bush moa, reaching about 20 inches (50 cm) in height and weighing around 20 pounds (9 kg), while the largest, the giant moa, could stand as tall as 10 feet (3 meters) and weigh up to 550 pounds (250 kg). This size range reflects adaptations to different habitats and diets, with larger species likely feeding on leaves and fruits from taller vegetation. Another critical morphological feature is their **feathers**. Unlike modern birds that have highly specialized feathers for flight, moa feathers were more primitive and likely served primarily for insulation and display. These feathers were often coarse and hair-like, providing warmth in New Zealand's temperate climate. The absence of flight feathers also indicates that moa did not require the lightweight yet strong structures necessary for flight, allowing them to allocate more resources to other bodily functions. The **skeletal structure** of moa is equally fascinating. Their skeletons show several adaptations typical of flightless birds. The keel bone, which in flying birds is prominent and serves as an anchor for flight muscles, is either greatly reduced or absent in moa. This suggests that these birds did not need the robust chest muscles required for wing movement. Additionally, their wings were vestigial, meaning they were much smaller and less functional compared to those of flying birds. The pelvis and leg bones, however, were robust and well-developed, indicating powerful legs adapted for walking and running. This skeletal arrangement points to a lifestyle focused on terrestrial locomotion rather than aerial mobility. These morphological features collectively paint a picture of how moa lived and interacted with their environment. Their size and skeletal adaptations suggest that they were well-suited to their habitats, ranging from forests to grasslands, where they could forage efficiently without the need for flight. The primitive nature of their feathers further underscores their evolutionary history as a distinct lineage of birds that diverged early from the common ancestor of modern birds. Understanding these physical characteristics provides valuable insights into the behavior and ecological roles that moa played in pre-human New Zealand ecosystems, highlighting their unique place in avian evolution and biodiversity.

Dietary Habits and Foraging Behavior

Dietary habits and foraging behavior are crucial aspects of understanding the physical characteristics and behavior of moa, the large, flightless birds that once inhabited New Zealand. Moa were herbivores, and their diet consisted mainly of leaves, seeds, fruits, and other plant materials. The specific dietary preferences varied among the different species of moa, but they generally foraged on a wide range of vegetation. The larger species, such as the giant moa (Dinornis robustus), likely fed on taller vegetation and trees due to their height advantage, while smaller species like the little bush moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis) focused on lower-growing plants and shrubs. Their foraging behavior was influenced by their physical adaptations. Moa had strong legs and powerful feet, which allowed them to move efficiently through dense forests and scrublands in search of food. Their beaks were robust and varied in shape among species; some had broad, flat beaks suitable for cropping leaves and fruits, while others had more pointed beaks that could be used to pluck seeds from cones or dig into soil for roots. The absence of predators in their native habitat meant that moa did not need to develop defensive behaviors or complex social structures related to foraging. Instead, they could focus on optimizing their feeding strategies to maximize nutrient intake. This is reflected in their digestive system, which was specialized to break down cellulose in plant material, allowing them to extract nutrients from tough, fibrous vegetation. Seasonal changes also played a significant role in shaping the dietary habits of moa. During times of abundance, such as spring and summer when vegetation was lush, moa would likely gorge on available food sources to build up fat reserves. In contrast, during periods of scarcity like winter, they would rely on stored fat reserves and possibly alter their foraging patterns to seek out more resilient plant species. Understanding these dietary habits and foraging behaviors provides valuable insights into the ecological niche occupied by moa and how they interacted with their environment. It highlights their unique adaptations that allowed them to thrive in New Zealand's diverse landscapes before their eventual extinction due to human activities and introduced predators. By examining these aspects of moa biology, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationships between species and their environments, as well as the importance of preserving biodiversity in modern ecosystems.

Social Structure and Mating Habits

The social structure and mating habits of the moa, a group of large, flightless birds that once inhabited New Zealand, are fascinating aspects of their biology that offer insights into their behavior and ecological roles. While direct observations are impossible due to their extinction, fossil records, archaeological findings, and comparative studies with other ratites provide valuable clues. Moa species likely exhibited a complex social hierarchy, with larger species such as the giant moa (Dinornis robustus) possibly dominating smaller ones like the little bush moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis). This hierarchical structure would have influenced their mating behaviors, where dominant individuals may have had priority access to mates and breeding territories. Mating habits among moas were likely seasonal, aligned with the availability of food resources which would have been crucial for successful breeding. During the breeding season, males may have engaged in competitive displays to attract females, similar to those observed in modern ratites like ostriches and emus. These displays could have included vocalizations, visual displays such as feather preening or posturing, and possibly even territorial fights among males. Female moas, on the other hand, would have selected mates based on criteria such as dominance status, health, and genetic diversity to ensure the best possible outcomes for their offspring. The nesting behavior of moas is another critical aspect of their social structure and mating habits. Females would have laid large eggs in shallow nests constructed from vegetation and soil, often in secluded areas to protect against predators. The incubation period would have been long, given the size of the eggs, and it is speculated that males might have played a role in incubation or at least in guarding the nest site from potential threats. This shared parental care would have been essential for the survival of the young moas, which would have been vulnerable to predation by introduced species like rats, cats, and humans when they eventually arrived in New Zealand. Understanding the social structure and mating habits of moas also sheds light on their ecological niches within pre-human New Zealand ecosystems. As herbivores, moas played a significant role in seed dispersal and vegetation management, influencing forest composition and structure. Their social behaviors would have further impacted these ecosystems through their movements and foraging patterns, contributing to nutrient cycling and habitat diversity. In conclusion, the social structure and mating habits of moas reflect a sophisticated and adaptive set of behaviors that allowed these birds to thrive in their native habitats for thousands of years. Despite their extinction, studying these aspects provides valuable insights into evolutionary biology, ecological dynamics, and conservation strategies for similar species today. By examining the intricate social lives of these ancient birds, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity of life on Earth and the importance of preserving biodiversity in modern ecosystems.

Extinction of Moa: Causes and Impact on Ecosystems

The extinction of the Moa, a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand, is a compelling example of how human activities can drastically alter ecosystems. This event was not the result of a single factor but rather a combination of several interconnected causes. Human overhunting and habitat destruction played a pivotal role in the decline of Moa populations, as early settlers exploited these birds for food and cleared their habitats for agriculture and settlement. Additionally, the introduction of predatory species by humans, such as rats, dogs, and cats, further threatened the Moa's survival by preying on them and their eggs. The ecological consequences of Moa extinction were profound, leading to significant changes in New Zealand's ecosystem balance and biodiversity. Understanding these factors is crucial for appreciating the full impact of human actions on native species and ecosystems. This article will delve into these aspects, beginning with the critical role of human overhunting and habitat destruction in the Moa's demise.

Human Overhunting and Habitat Destruction

Human overhunting and habitat destruction are pivotal factors in the extinction of many species, including the Moa, a group of large, flightless birds that once inhabited New Zealand. The arrival of humans in the 13th century marked the beginning of a catastrophic period for these birds. Overhunting by early Polynesian settlers, who saw the Moa as a valuable source of food and resources, led to their rapid decline. The Moa's large size and lack of fear towards humans made them easy prey, and their populations were quickly depleted. Additionally, the introduction of invasive species such as rats, dogs, and pigs further exacerbated the decline by competing for resources and preying on Moa eggs and chicks. Habitat destruction also played a crucial role in the Moa's demise. As human settlements expanded, forests were cleared for agriculture and other uses, reducing the available habitat for the Moa. This not only limited their food sources but also fragmented their populations, making it difficult for them to find mates and maintain viable breeding groups. The loss of habitat disrupted the delicate balance of New Zealand's ecosystems, leading to cascading effects on other native species that depended on the Moa for various ecological roles. The impact of these human activities on ecosystems was profound. The Moa played a significant role in seed dispersal and nutrient cycling, and their absence led to changes in forest composition and structure. Without the Moa to disperse seeds, certain plant species declined or disappeared, affecting other herbivores that relied on these plants for food. This ripple effect extended through multiple trophic levels, altering predator-prey dynamics and leading to further extinctions among other native species. Moreover, the loss of the Moa had long-term consequences for New Zealand's biodiversity. The absence of these large herbivores allowed certain plant species to overgrow, altering fire regimes and increasing the risk of wildfires. This, in turn, affected soil quality and further degraded habitats, creating a cycle of ecological degradation that persists to this day. In conclusion, human overhunting and habitat destruction were the primary drivers of the Moa's extinction, with far-reaching impacts on New Zealand's ecosystems. These events serve as a stark reminder of the profound influence humans can have on natural environments and underscore the importance of conservation efforts to protect remaining biodiversity. Understanding these historical lessons is crucial for developing effective strategies to mitigate current and future threats to species and ecosystems worldwide.

Introduction of Predatory Species by Humans

The introduction of predatory species by humans has been a pivotal factor in the extinction of many native species, including the iconic moa of New Zealand. This phenomenon, often referred to as "invasive species introduction," has far-reaching and devastating consequences on ecosystems. When humans intentionally or unintentionally introduce non-native predators, such as rats, cats, dogs, and stoats, into an environment where they have no natural predators or competitors, these invaders can rapidly disrupt the delicate balance of the ecosystem. In the case of New Zealand, the arrival of Polynesian settlers around the 13th century marked the beginning of a catastrophic sequence of events for the moa population. These large, flightless birds had evolved in isolation for millions of years without significant predation pressure, making them highly vulnerable to introduced predators. The Polynesians brought with them rats (Rattus exulans), which quickly spread across the islands and began preying on moa eggs and chicks. Later, European settlers introduced additional predators like cats, dogs, and stoats (Mustela erminea), further exacerbating the decline of moa populations. These introduced predators not only directly hunted moa but also competed with them for food resources and habitat, leading to a rapid decline in their numbers. By the early 15th century, the moa had become extinct due to this combination of direct predation and indirect competition. The loss of such a keystone species had profound impacts on New Zealand's ecosystem, leading to changes in vegetation patterns, alterations in nutrient cycling, and a cascade of other ecological consequences that continue to be felt today. The story of the moa serves as a stark reminder of the irreversible damage that can result from human activities involving the introduction of non-native species into pristine environments, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts and responsible land management practices to protect native biodiversity.

Ecological Consequences of Moa Extinction

The extinction of the moa, a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand, has had profound ecological consequences that continue to shape the country's ecosystems today. The moa, which included several species ranging from the small Little Bush Moa to the towering Giant Moa, played a crucial role in New Zealand's pre-human ecosystem. As herbivores, moa were key seed dispersers and browsers, influencing the composition and structure of forests and grasslands. Their feeding habits helped maintain the diversity of plant species by dispersing seeds through their droppings, often in new locations far from the parent plants. This process facilitated the spread and establishment of various plant species, contributing to the rich biodiversity of New Zealand's flora. The loss of these birds led to significant changes in vegetation patterns. Without moa to disperse seeds, many plant species that relied on them for propagation began to decline or became restricted to smaller areas. This shift has been particularly evident in the decline of certain tree species like the Matai and Rimu, which were heavily dependent on moa for seed dispersal. The absence of these large herbivores also allowed other plant species that were less palatable to moa to overgrow and dominate landscapes, altering the overall vegetation structure and reducing plant diversity. Furthermore, the extinction of moa had cascading effects on other components of the ecosystem. Predators such as the Haast's Eagle, which relied heavily on moa as a food source, also went extinct shortly after the moa disappeared. This ripple effect extended to other species that were part of the food web, leading to a broader loss of biodiversity. The reduction in seed dispersal and browsing activities also impacted soil health and nutrient cycling, as moa droppings were an important source of nutrients for many plants. In addition, the ecological niches left vacant by the moa have not been fully occupied by other native species. Introduced herbivores like deer, goats, and sheep have filled some of these niches but do not replicate the unique ecological roles of moa. These introduced species often cause overgrazing and habitat degradation, further exacerbating the ecological imbalance caused by the moa's extinction. Today, conservation efforts in New Zealand aim to restore some of the ecological functions lost with the moa's extinction. For example, reintroducing native birds that can act as seed dispersers and browsers, such as the Kakapo and Weka, is seen as a way to partially restore these ecological processes. However, these efforts are challenging due to the complexity of reestablishing historical ecological relationships and the presence of invasive species that compete with native wildlife for resources. In conclusion, the ecological consequences of moa extinction are multifaceted and far-reaching, impacting plant diversity, vegetation structure, predator-prey relationships, and overall ecosystem health. Understanding these impacts is crucial for informing conservation strategies that aim to restore and maintain the integrity of New Zealand's unique ecosystems.